The Mesoratic text does not include Psalm 151 into the Psalter. It was known in Greek, Latin, and Syriac translation before the discovery of the Dead Sea Psalm Scrolls. Psalm 151 in the scroll (11Q5 Col. XXVIII) is longer than that of the Greek. It has been published with discussion by J. A. Sanders (1963). Sanders defines Psalm 151 in the scroll as “a poetic midrash on 1 Sam 16:1-3,” composing a new poetry out of older biblical passages. I will discuss Psalm 151 in the scroll (11Q5 Col. XXVIII) with the discussion of the midrash interpetation of 1 Sam 16:1-13.

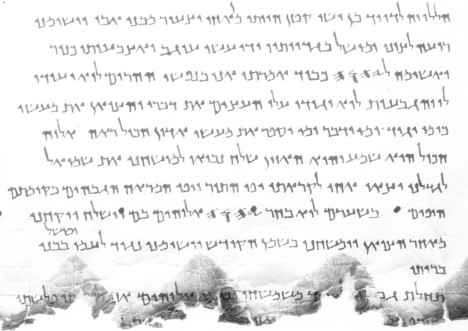

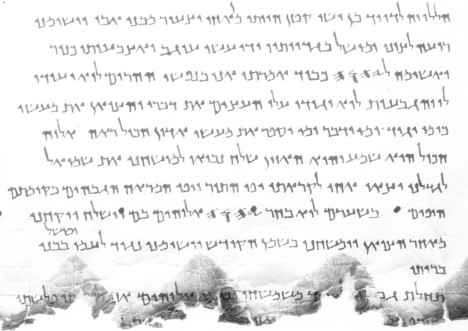

Manuscript of 11Q5 Col. XXVIII (Psalm 151A and B)

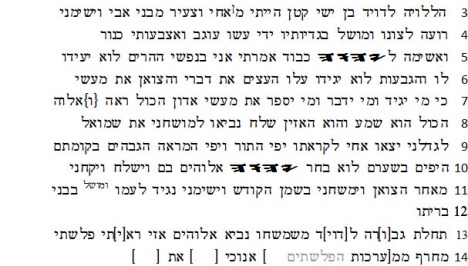

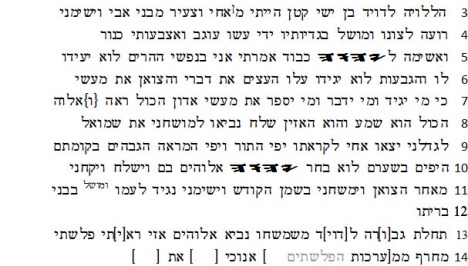

Transcription of 11Q5 Col. XXVIII (Psalm 151 A and B)

The transcription is taken from Dead Sea Scrolls Electronic Library (Revised Edition; Leiden: Brill, 2006).

Translation of 11Q5 Col. XXVIII (Psalm 151 A and B)

3. Hallelujah! A psalm of David, son of Jesse. I was smaller than my brothers, youngest of my father’s sons. So he made me a

4. shepherd for his sheep, a ruler over his goats. My hands fashioned a pipe, my fingers a lyre,

5. and I glorified the Lord. I said to myself, “The mountains do not testify

6. to Him, nor do the hills proclaim.” So-echo my words, O trees, O sheep, my deeds!

7. Ah, but who can proclaim, who declare the deeds of the Lord? God has seen all,

8. heard and attended to everything. He sent his prophet to anoint me, even Samuel,

9. to raise me up. My brothers went forth to meet him: handsome of figure, wondrous of appearance, tall were they of stature,

10. so beautiful their hair-yet the Lord God did not choose them. No, He sent and took me

11. who followed the flock, and anointed me with the holy oil. He set me as prince to His people, vacat ruler over the children of

12. His covenant vacat

13. [Dav]id’s first mighty d[ee]d after the prophet of God had anointed him. Then I s[a]w the Philistine,

14. throwing out taunts from the [enemy] r[anks ]

The translation is taken from Dead Sea Scrolls Electronic Library (Revised Edition; Leiden: Brill, 2006).

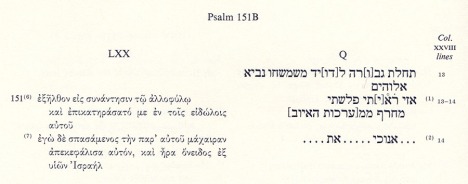

LXX and 11Q5 Psalm 151 A by Sanders

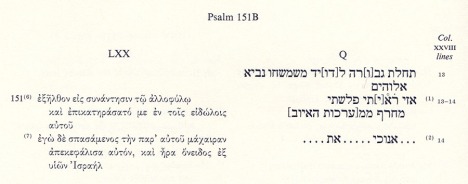

LXX and 11Q5 Psalm 151 B by Sanders

Sander’s translation of LXX and 11Q5 Psalm 151 A and B here. For variant translations of Psalm 151 A, see Sanders’ book (pp. 100–103).

This psalm consists of two parts: (1) David’s anointing by God’s messenger (vv 1-5); and (2) David’s defeat of the Philistine warrior (vv 6-7). As we can see from the comparision of LXX Psalm 151 with 11Q5 Psalm 151 (Sanders divides 11Q5 Col. XXVIII into two parts: Psalm 151 A and 151 B), Psalm 151 in the scroll is different from that of the Greek. Sanders points the beauty and integrity of the Hebrew psalm in the parallelism between v. 1 and v. 7:

Whereas Jesse, David’s father, had made the lad shepherd and ruler over his flocks, God made him leader and ruler over his people. This parallel structure is truncated in the Greek to the bland statement in Greek verse 1, “I tended my father’s flock” [my emphasis].

This parallelism shows the contrast between Jesse’s intention and God’s intention. The most interesting omission in the Greek is the section appering in the scroll in verses 2b and 3, and this portion reinforces the contrast that is found in the parallelism:

David’s election in 1 Sam 16:7 is the crux of the poetic midrash: “The Lord looks upon the heart” (יהוה יראה ללבב). As Sanders argues, however, the biblical passage fails to state what God saw in Dvid’s heart. The portion that is preserved in the scroll (vv. 2b-3) supplies the poetic midrash. David rendered glory to the Lord within his soul (v. 2b) event though he is insignificant in the outward appearance. The symbols in the next verse (v. 3), in my view, demonstrate a rhetorical contrast between significance and insignificance in the outward appearance:

The mountains do not witness to him, nor do the hills proclaim; the trees have cherished my words and the flock my words.

David is identified with the insignificant trees and flock. The Lord who can see into the heart has seen and heard everything David has done and said (v. 4). Thus, God heeded David’s piety of soul by sending the prophet Samuel to take him from behind the flock to make him a great ruler. In this respect, the emphasis on David as a musician, especially in the Hebrew version, is significant; David rendered glory to the Lord within his soul. The tradition about David’s responsibility for making musical instruments is attested in 1 Chr 23:5, 2 Chr 7:6; 29:26-27, Neh 12:36, and Psalm 151:2.

The Hebrew version provides more sophistigated midrash interpretatation of 1 Sam 16:1-3 than the Greek version. Sanders concludes his discussion on the main theme of Psalm 151 A (11Q5 Col. XXVIII) as follows:

Psalm 151 A [in the scroll] makes a great point of insisting that David, unlike his brothers, is samll and humble (vv. 5 and 6), but in his soul wants only to glorify God wih his homemade lyre.

God chose not the brothers; rather he chose the little shephered behind Jesse’s flock and exalted him as leader of the covenant people (בני ברית).

Reference List

Charlesworth, J. H. and J. A. Sanders. “Psalm 151.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. 2 vols. Edited by J. H. Charlesworth. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1983, 1985. Vol. 2, 612-15.

Flint, Peter W. The Dead Sea Psalms Scrolls and the Book of Psalms. Leiden: Brill, 1997.

Harrington, Daniel. “Psalm 151.” In Harper’s Bible Commentary. James L. Mays. San Francisco: Harper & Row, c1988.

Sanders, J. A. The Dead Sea Psalms Scroll. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967.

________. The Psalms Scroll of Qumran Cave 11 (11Qpsa). Oxford: Clarendon, 1965.

Filed under: Manuscripts | 5 Comments »

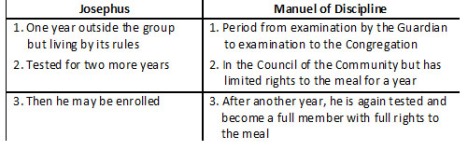

Eleazar Sukenik (1947) was the first scholar who proposes that the scrolls might have a connection with the Essenes described by the historian Josephus. He supposed the connection between Qumran and the Essenes when he read the Manual of Discipline, which defined the way of life for a wilderness sect. The principal argument for identifying the inhabitants of Qumran as Essenes is that the beliefs and practices of the Essenes, as reported in ancient sources (Josephus, Pliny, Philo, and others), agree remarkably well with the beliefs and practices presented and reflected in the Dead Sea Scrolls. See also

Eleazar Sukenik (1947) was the first scholar who proposes that the scrolls might have a connection with the Essenes described by the historian Josephus. He supposed the connection between Qumran and the Essenes when he read the Manual of Discipline, which defined the way of life for a wilderness sect. The principal argument for identifying the inhabitants of Qumran as Essenes is that the beliefs and practices of the Essenes, as reported in ancient sources (Josephus, Pliny, Philo, and others), agree remarkably well with the beliefs and practices presented and reflected in the Dead Sea Scrolls. See also

First, Lawrence Schiffman is responsible for the Qumran-Sadducees hypothesis. What is his eveidence? According to him, several of the legal views on purity defended in Some of the Works of the Torah (4QMMT) as those of the authors-the people of Qumran-have significant overlaps with positions that rabbinic literature attributes to the Sadducees. VanderKam comments on this evidence as follows:

First, Lawrence Schiffman is responsible for the Qumran-Sadducees hypothesis. What is his eveidence? According to him, several of the legal views on purity defended in Some of the Works of the Torah (4QMMT) as those of the authors-the people of Qumran-have significant overlaps with positions that rabbinic literature attributes to the Sadducees. VanderKam comments on this evidence as follows: Second,

Second,